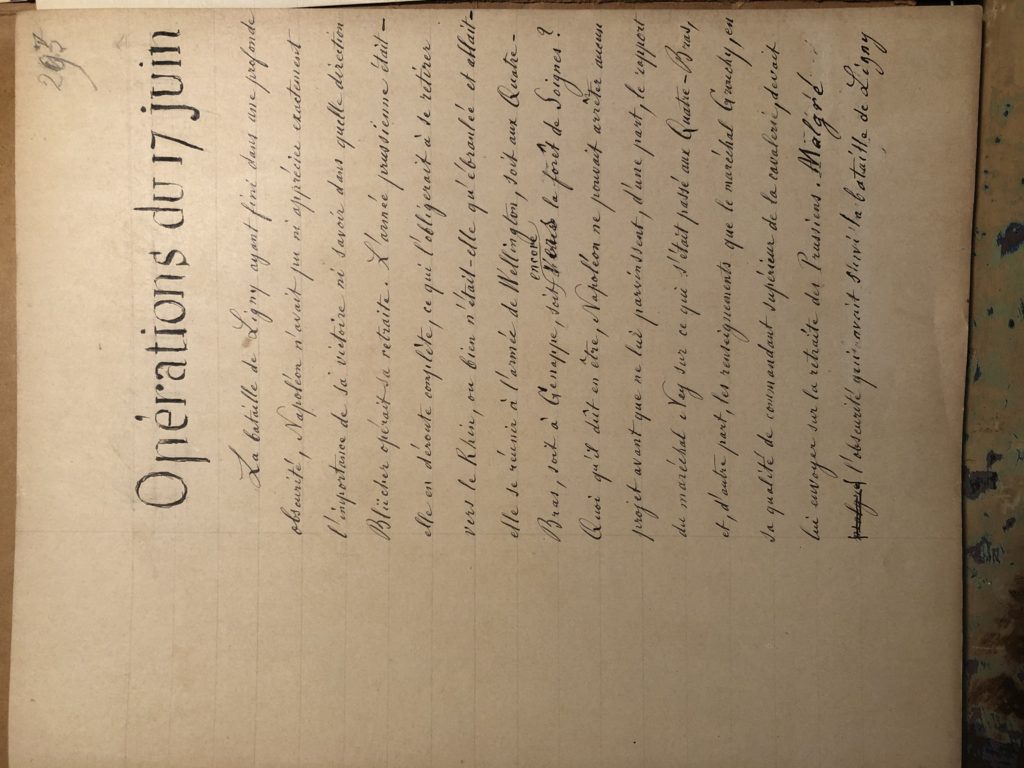

June 17 - Operations of June 17

Napoleon moved to Quatre-Bras, and then led the chase of the English with personal command of some squadrons of cavalry and horse-artillery. Following him was 1st Corps, 2nd Corps, 6th Corps and the Guard. In the afternoon the rain started and continued through the night. Upon arrival south of Mont St. Jean near Plancenoit, Napoleon feared that Wellington would not give battle, and retreat until achieving a chance to combine with the Prussians. Thus, Napoleon deployed heavy cavalry and artillery in a manner sufficient for the Anglo-Dutch army to reveal its presence; it was more than a rear-guard. Napoleon hoped for a major battle the next day.

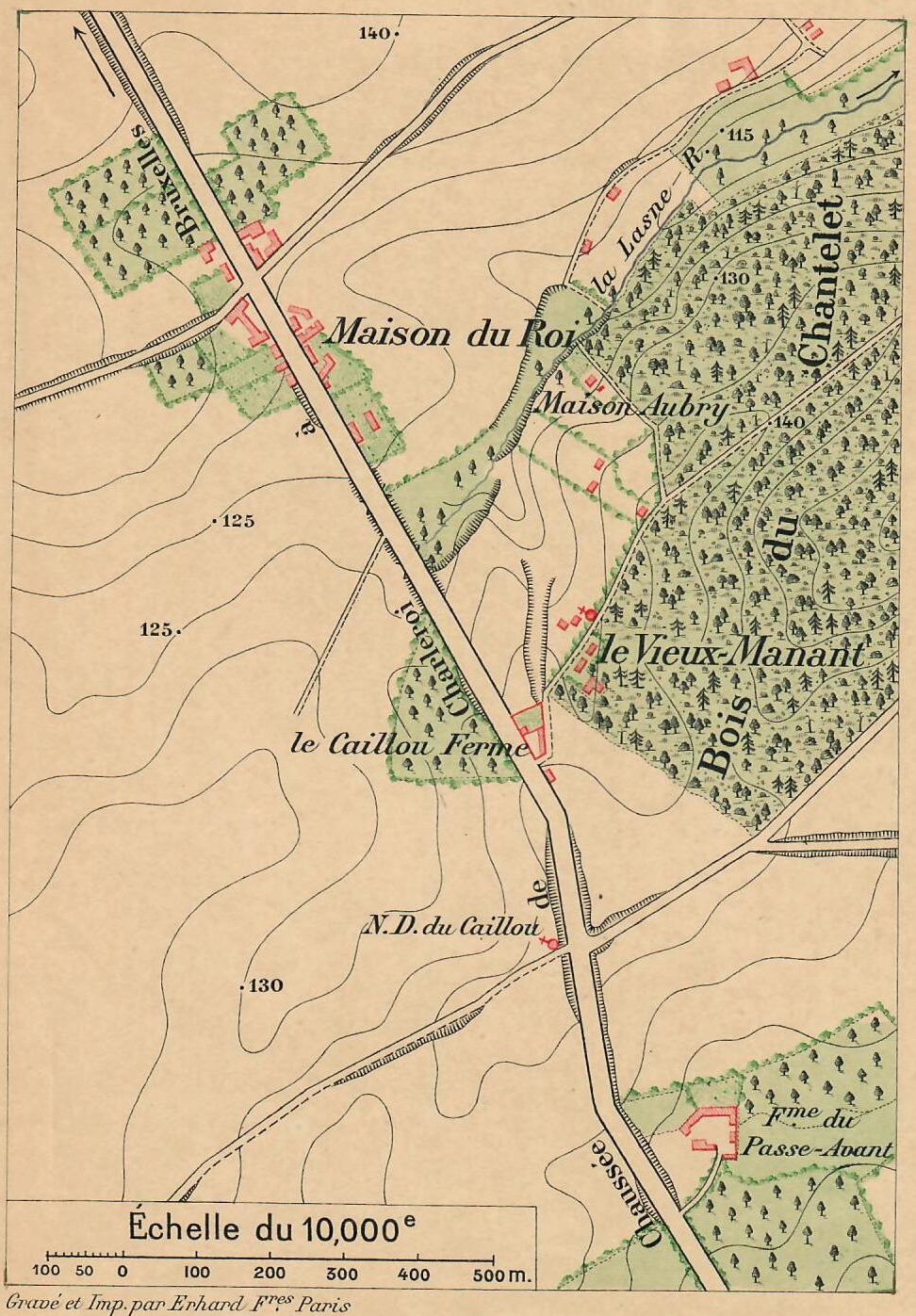

Napoleon and his entourage set up at the farm of Caillou.

In the 19th Century, one of the most studied aspects of the campaign were the actions of Grouchy. Stoffel’s Waterloo study gave it considerable attention. His interest may have been heightened by his father, Augustin, who was the Colonel of a Swiss regiment in Vandamme’s 3rd Corps.

Stoffel died prior to the publication of his work, and lacking heirs, it was purchased. Subsequently, an article, titled the Operations of 17th of June, was published in 1909 by Revue Militaire Générale. The author has both an original, and a typesetter ready, draft of this article:

If we wonder if copies in the archives that originated with Grouchy are pristine, or if the Registre du major-général is complete, and wonder why Grouchy may have hid orders for decades, we must consider the life he lived post-Waterloo. Immediately, he was blamed for the disaster.

The following appeared in the June 26th edition of Journal de l’Empire:

It is said that it was the Prussian corps of General Bulow that decided the fate of the battle of the 18th. By a fatal error, this corps was taken during the maneuvers of the battle, for the corps of Marshal Grouchy, which was to arrive on the right wing of the French army. It is asserted that the dispatch of the Emperor, which ordered Marshal Grouchy to attack the corps of General Bulow, was intercepted by the Prussians.

Napoleon claimed to send recall orders to Grouchy, which is generally not believed. Napoleon said in his memoirs:

At ten o’clock in the evening, I sent an officer to Marshal Grouchy whom I supposed to be at Wavres, in order to let him know that there would be a great battle the next day; that the Anglo-Dutch army was in position in front of the forest of Soignes, with its left resting on the village of La Haye; that I ordered him to detach from his camp at Wavres a division of 7,000 men of all arms and sixteen guns, before daylight, to go to Saint-Lambert to join the right of the Grand Army and co-operate with it; that, as soon as he was satisfied that Marshal Blücher had evacuated Wavres, whether to continue his retreat on Brussels or to go in any other direction, he was to march with the bulk of his troops to support the detachment which he had sent to Saint-Lambert.

Stoffel’s article likewise mentions this order, and even quoted the route given the carrier, “sur Wavre, au nord de Gembloux.” Napoleon also discussed with Gourgaud in exile having sent the orders. In Grouchy’s Relation Succincte, there is a long report on the capture of the orders with various testimonies.

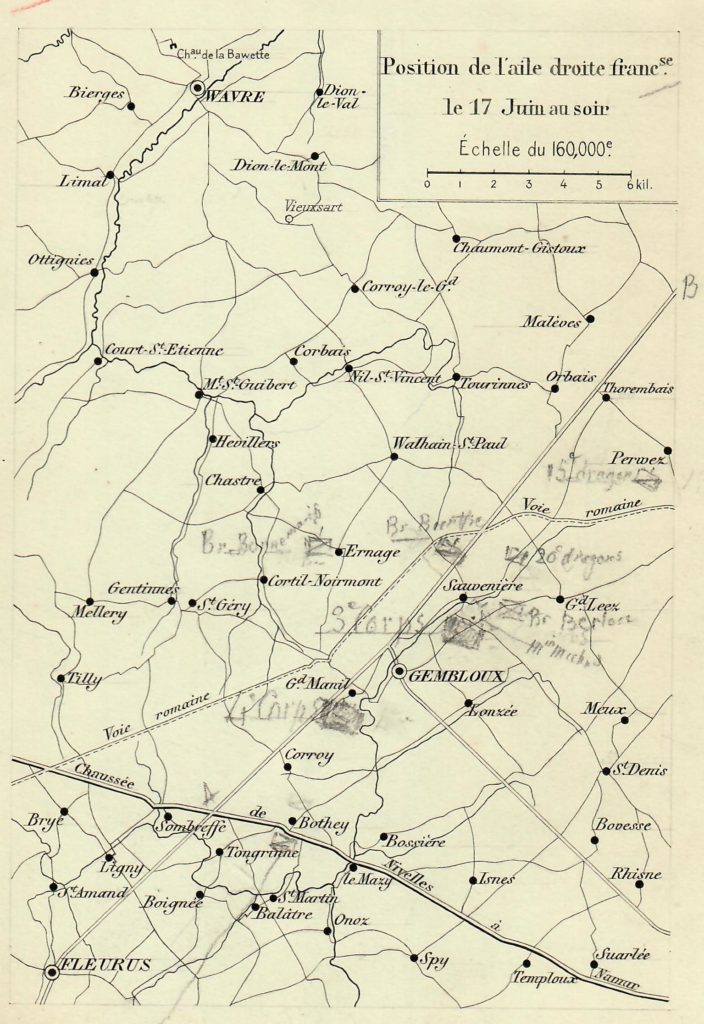

There is no evidence Grouchy received orders to send any portion of his force towards Napoleon. In fact, Grouchy’s force made barely any progress on June 17:

Grouchy’s performance was not inspiring, but he was not the cause of Napoleon’s defeat. Today, this is generally believed. But in the 19th century, it was so clear that Grouchy was the root cause of the disaster that the following appeared in a French grammar lesson in 1869:

Les alliés auraient été vaincu à Waterloo, sans un malentendu du général Grouchy.

Translated: The allies would have been defeated at Waterloo without a misunderstanding of General Grouchy.

While Grouchy struggled to command his forces and find the enemy, the Prussians tenaciously retreated to a position where they would be able to assist Wellington.

Blücher and Wellington continued to work together.

Napoleon didn’t even know where Grouchy was.