June 10 - The Two Orders

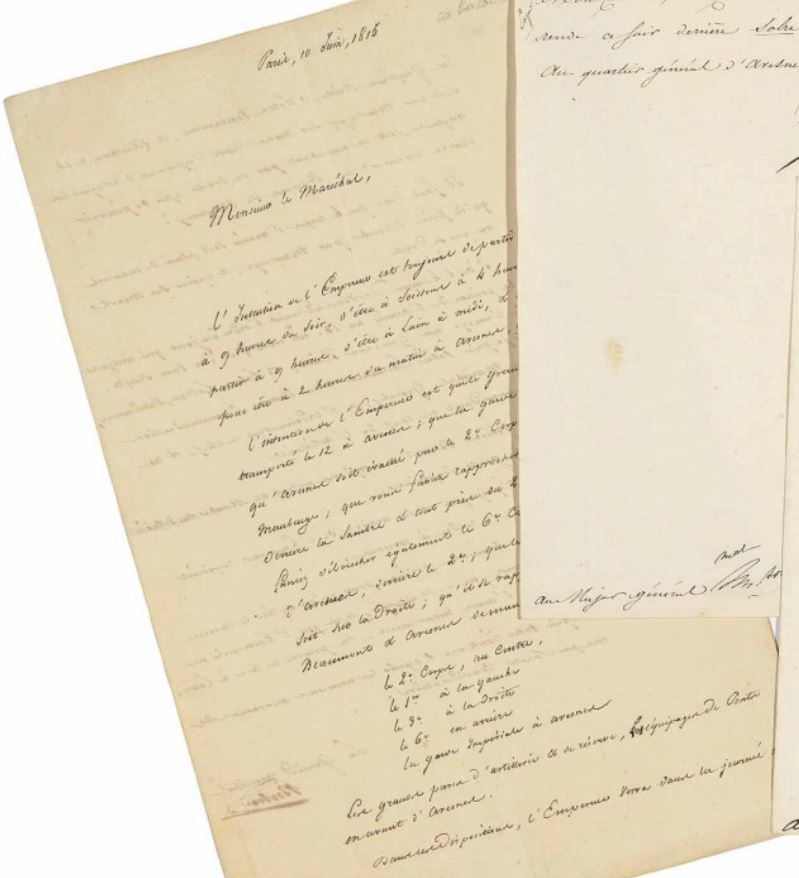

On June 10, 1815, Napoleon dictated two orders for the final concentration of the Armée du Nord on the Sambre.

As Soult was in Lille, Bertrand fulfilled the role of having the orders transcribed and distributed.

The first plan transcribed describes a disposition for the Army on the 12th arranged for an advance on Mons, which was where the front of the army pointed, though Napoleon explicitly stated that it could also move to its right, on Charleroi.

The plan was put into a formal letter to Soult:

The second order dictated defined the Position of the Army on June 13 and was a plan for three balanced columns on parallel roads to Charleroi. Bertrand’s registry indicates this plan was sent to the Army and Soult, and the copy Vandamme received is in the archives, as well as the cover letter to the Ordre du Jour for Position of the Army on the 13th that Reille received.

While Bertrand’s notes contain a disposition for June 12, as well as a detailed draft of the above letter to Soult, there is no indication that the Mons plan was sent to any General.

It is also clear that on June 10, Napoleon and Bertrand expected Soult to receive the drafted orders in Laon. And, in fact, Bertrand did not send orders directly to Grouchy who was headquartered in Laon, but to Soult. Soult was expected to send duplicates to the Infantry Corps, and forward the orders to Grouchy and other elements in Laon.

That Soult was expected in Laon is also supported by Gérard, who, despite being in Metz, had also come to believe Soult would be in Laon, and addressed his June 10 report to Soult in Laon.

During this period, it was remarkable how efficient the postes and estafette services could be, as long as the recipient is there to receive it.

___

In 1821, after Napoleon’s death, Bertrand returned to Europe; he arrived in Portsmouth on August 1. On August 6, Bertrand and his family traveled to London where they took residence at Brunet’s Hotel of Leicester Square, along with Montholon and his family. During their stay in England, Bertrand and Montholon were often visited by various officers and government officials.

On September 15, Hobhouse visited Bertrand, and recounted this visit in his diary:

I called with D. Kinnaird on Count Bertrand, at Brunet’s Hotel. Found him and his Countess, his brother, and another person there. The Countess ill with a cough – a pale, tall, thin, agreeable-looking woman, of a certain age. The Count very solicitous about her health.

Bertrand drew near to me and spoke frankly about my book. Said the Emperor saw at once that il sortait de la classe; that he saw I had had recourse to good informants. That he, at first, had resolved to answer the book and to correct many points of which he alone has knowledge, having the reins of Government, and could give a just account; that he observed I had altered my opinions as to the libéraux in the second edition, and had seen that they did wrong to suspect the Emperor and to debate about liberty when they should be defending their country against the foreigners. This alluded to a note which Constant furnished me with.

Bertrand told me that the reason why Napoleon discontinued writing his remarks on my book was, first, he took up the employment, and wrote those things which all the world knows. I did not ask him what he really wrote, but Montholon told Kinnaird that he wrote the account of the battle of Waterloo, which Phillips published. The other reason was that he could not write on my book without exposing the treachery of many men still about the French Court, which he did not wish to do. I said, “Fouché, for instance.” “Yes,” said Bertrand, “I myself introduced by the back stairs to Napoleon the courier who had Fouché’s dispatches to the enemy – eight days before the battle of Waterloo.”Hobhouse, Recollections of a Long Life, Volume II, 1816-1821, page 157

Eight days before the battle of Waterloo was June 10, 1815.

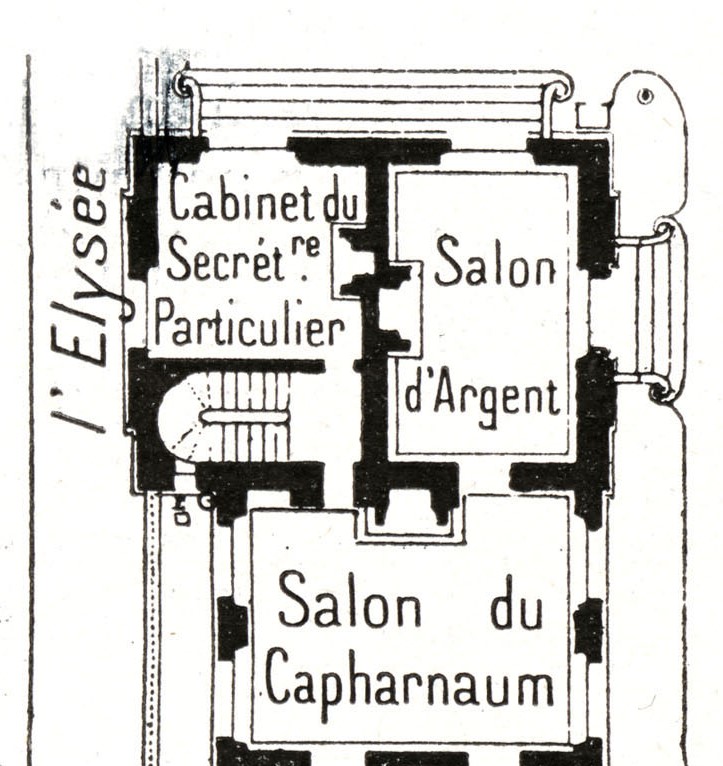

The rear of the left wing of the Palais de l’Elysée, Napoleon’s residence in Paris during 1815. It is possible that Napoleon and Bertrand worked on the final concentration orders in the Salon d’Argent.

Hobhouse’s Recollections of a long life were published 40 years after his death. No one was living to corroborate the content of his diaries. During his lifetime, he published letters he wrote from Paris which caused quite a stir. He was a political reformer during a polarizing time. His opinions gained wide acclaim and derision, but his recounting of events and facts has never been suspect. Of course, here he repeats a story provided by Bertrand, who did not relate this story to anyone else. Bertrand was not an opportunist, and though compiled a very respected Cahiers de Sainte-Hélène, he did not publish them.